Dissociation

Grounding Techniques Menu

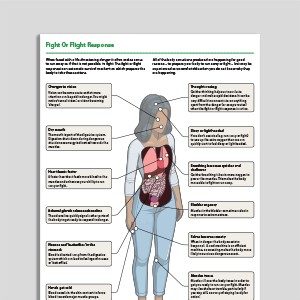

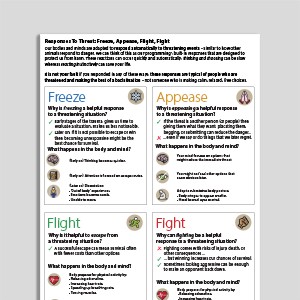

Fight Or Flight Response

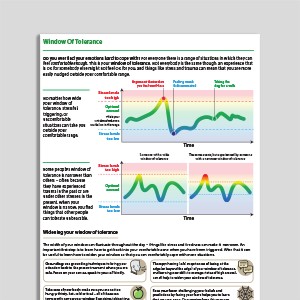

Window Of Tolerance

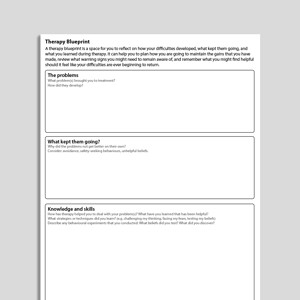

Therapy Blueprint (Universal)

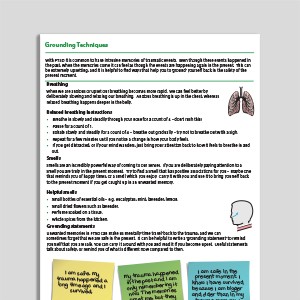

Grounding Techniques

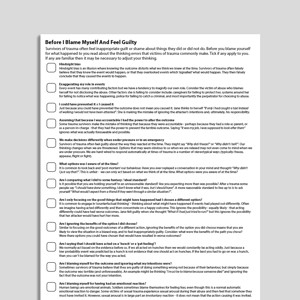

Before I Blame Myself And Feel Guilty

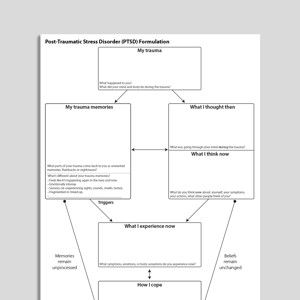

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Formulation

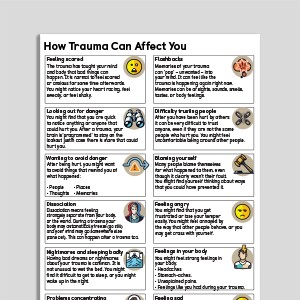

How Trauma Can Affect You (CYP)

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Relaxation

Responses To Threat: Freeze, Appease, Flight, Fight

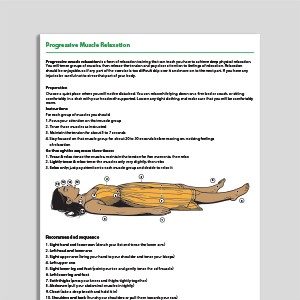

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

Reactions To Trauma

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Client Workbook

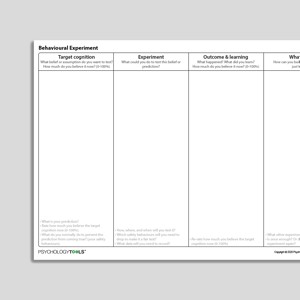

Behavioral Experiment

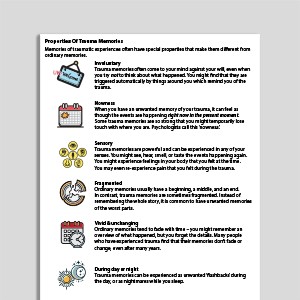

Properties Of Trauma Memories

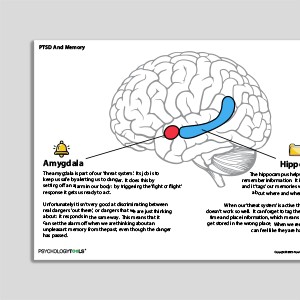

PTSD And Memory

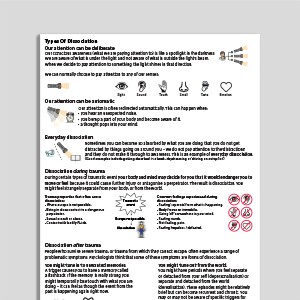

Types Of Dissociation

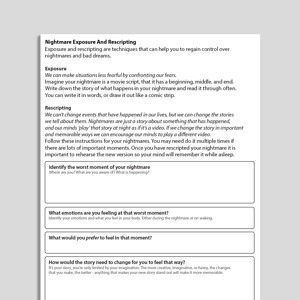

Nightmare Exposure And Rescripting

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Punitiveness

PTSD Linen Cupboard Metaphor

Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

Trauma And Dissociation

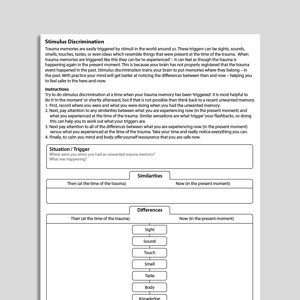

Stimulus Discrimination

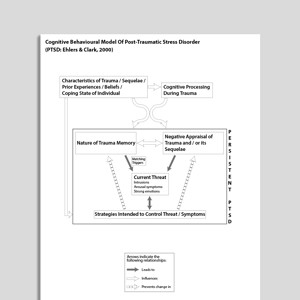

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD: Ehlers & Clark, 2000)

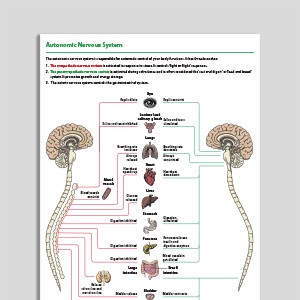

Autonomic Nervous System

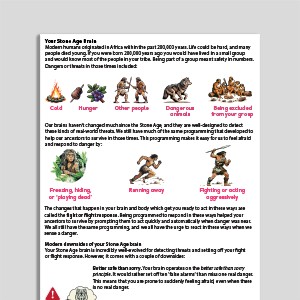

Your Stone Age Brain

Intrusive Memory Record

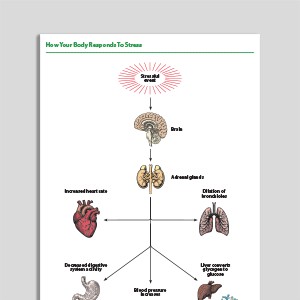

How Your Body Responds To Stress

Hotspot Record

PTSD Film Projection Metaphor

Progressive Muscle Relaxation (Archived)

Your Stone Age Brain (CYP)

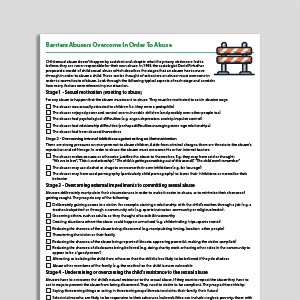

Barriers Abusers Overcome In Order To Abuse

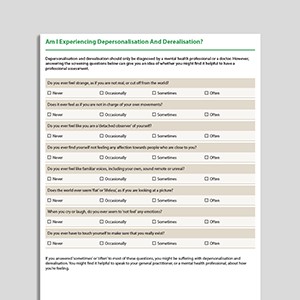

Understanding Depersonalization And Derealization

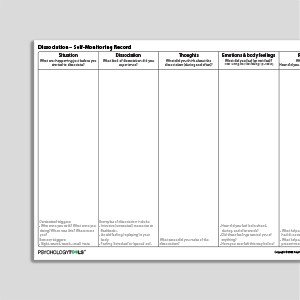

Dissociation - Self-Monitoring Record

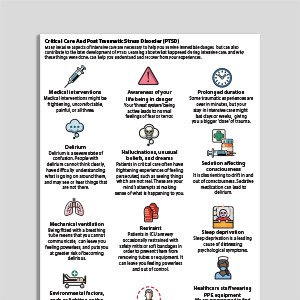

Critical Care And PTSD

Grounding Statements (Audio)

Sensory Grounding Using Your Five Senses (Audio)

Rewind Technique

Trauma, Dissociation, And Grounding (Archived)

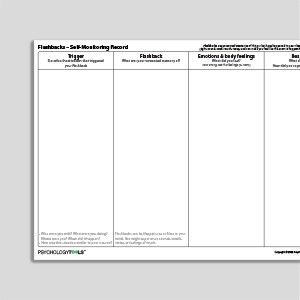

Flashbacks - Self-Monitoring Record

Am I Experiencing Depersonalization And Derealization?

[Free Guide] Critical Illness Intensive Care And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

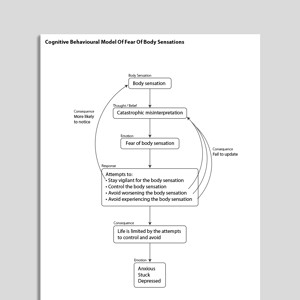

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Fear Of Body Sensations

Recognizing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

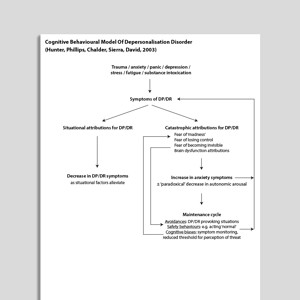

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Depersonalization (Hunter, Phillips, Chalder, Sierra, David, 2003)

Grounding Objects (Audio)

Recognizing Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder (DPD)

Sensory Grounding Using Smells (Audio)

Symptom Tracker

Stimulus Discrimination (Audio)

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Assessment

-

Brief Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-B)

| Dalenberg, Carlson | 2010

- Scale

- DES-B (Dalenberg C, Carlson E, 2010) modified for DSM-5 by C. Dalenberg and E. Carlson.

-

Dissociative Experiences Scale – II (DES-II)

| Carlson, Putnam | 1993

- Scale

- Carlson, E.B. & Putnam, F.W. (1993). An update on the Dissociative Experience Scale. Dissociation 6(1), p. 16-27.

-

Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D)

| Schauer, Schalinski, Elbert | 2015

- Scale (English)

- Scale (German)

- Scale (Norwegian)

- Reference Schalinski, I., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2015). The Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6

Guides and workbooks

- Live within your window of tolerance | Laura Kerr | 2015

Information Handouts

- What is dissociation and what to do about it? | Washington.edu

- Dissociation and dissociative disorders | Mind | 2019

- Trauma related dissociation: an introduction | International Society For The Study Of Trauma And Dissociation

- Dissociation in children and teens | Beacon House | 2020

- Dissociation and trauma in young people | Orygen

- Functional dissociative seizures | Neurosymptoms: Jon Stone | 2014

Treatment Guide

- Working with dissociation: some powerful practical tips | Russ Harris

What is dissociation?

When functioning normally, our conscious experience is supported by a number of integrated processes: sensations and perceptions, sense of self, memories, feelings and actions. Dissociation refers to an experience or feeling of disconnection that disrupts this integrated experience: “a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment” (APA, 2013). Dissociation is often key in the presentation of individuals who have undergone significant trauma (Steele & van der Hart, 2013).

Signs and symptoms of dissociation

It is possible to place acute episodes of dissociation on a continuum from benign and possibly pleasant experiences to those that are distressing and pathological (Carlson & Putnam, 1993; Kennedy & Kennerley, 2013).

Benign examples of dissociation include:

- Daydreaming.

- Going on ‘automatic pilot’ whilst walking or driving.

- Becoming completely absorbed in an activity, e.g. when reading or watching a film.

- Going ‘blank’ mentally.

Clinically-relevant examples of dissociation include:

- Being unable to remember recent or past events (amnesia).

- Depersonalisation (feeling detached from oneself) .

- Derealisation (feeling detached from the world).

- Being unable to perform actions or skills that are normally under voluntary control.

- Identity confusion (feeling that your self is incoherent and not continuous over time).

- Intrusive traumatic memories (flashbacks).

The many clinical manifestations of dissociation have a number of common features. Dissociation is often accompanied by somatic symptoms that can affect movement, perception, sensation and appetite. Individuals also often have a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Dissociation features prominently in a range of clinical conditions:

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Depersonalization Derealization Disorder

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Psychosis

- Eating disorders

- Panic (e.g. derealisation during panic attacks)

What causes dissociation?

Researchers have linked experiences of detachment to specific neuro-biological states (e.g. Nijenhuis & den Boer, 2010; Schauer & Elbert, 2010). There is agreement that dissociation can be a protective mechanism that helps individuals to survive overwhelming situations, emotions or memories. Under threatening conditions it may be helpful to be in a state of vigilance, but to emotional and physical inhibition which prevents you from doing something that might endanger you further, such as provoking an attacker, or which may help to reduce pain or suffering when injury is unavoidable (Schauer & Elbert, 2010). Whilst this state is thought to help people to survive a threatening situation, it can impair the formation of autobiographical memories and lead to poorly integrated, intrusive and distressing trauma memories (Kennedy & Kennerley, 2013).

Cognitive theories support the idea that detachment – being taken away from the here and now – is protective, as it means that all the information and emotions do not have to be attended to and processed (Kennedy & Kennerley, 2013). In clinical conditions episodes of dissociation typically occur when emotions become overwhelming, acting as an emotional pressure relief valve that helps the person to cope. Dissociation itself can be aversive thought, and maladaptive behaviours can be negatively conditioned through a link with dissociation. These include self-harm, bingeing, starving oneself or drug use. They might be performed to escape an overwhelming emotion (i.e. to induce dissociation), or to come out of a ‘numbness’ (i.e. to return from dissociation; Kennerley & Kishcka, 2013).

Psychological Models And Theory Of Dissociation

Recognisable descriptions of dissociative episodes are found in 17th and 18th Century documents, with the first analytical accounts of ‘disintegrated’ or split consciousness appearing in the 1800s (Kennedy & Kennerley, 2013). Pierre Janet was the first to document traumatic flashbacks and the way in which personality states could switch dramatically with their onset (ibid). Breuer and Freud (1893) made a direct link between traumatic events, traumatic memories and ‘hysterical’ (dissociative) phenomena.

“The memories which have become the determinants of hysterical phenomena persist for a long time with astonishing freshness and with the whole of their affective colouring… these memories, unlike other memories of their past lives, are not at the patients’ disposal. On the contrary, these experiences are completely absent from the patients’ memory when they are in a normal psychical state”

More recent theories have tried to categorize different kinds of dissociation, or split a continuum of dissociation into pathologies or conditions with ‘greater’ degrees of dissociation (e.g. dissociative personality disorder) as compared to more quotidian experiences people may have (being absorbed in a book, day dreaming, driving without being fully aware; ibid). Some have argued that everyday experiences such as day-dreaming and absorption should not be classed as true dissociation. Current theory suggests that there is continuum of dissociation that can become pathological at the extreme end and that “any specific presentation of dissociation can be experienced along a continuum of severity” (Kennedy & Kennerley, 2013).

Holmes and colleagues (2005) proposed a distinction between two kinds of dissociative experience: detachment and compartmentalization:

“Detachment constitutes a mental state with a core neurophysiological profile, unlike compartmentalization, which can exist in many forms… compartmentalization refers to a lack of integration of information within the cognitive system, while detachment refers to an experienced state of disconnection from the self or environment.”

- Detachment describe experiences where the person feels separated or disconnected. Examples include depersonalisation, derealisation, and out of body experiences. The individual has an experience of being separated from their body, the world, or themselves. It may include emotional numbing. Detachment includes peri-traumatic dissociation and the intrusive flashbacks experienced by those with PTSD. This is because flashbacks are likely caused by poorly processed autobiographical memories due to dissociation (detachment) at the time of the trauma and flashbacks often include an experience or sense of detachment.

- Compartmentalization describes the inability to control cognitive, motor or somatic processes that would normally be under voluntary control. Examples include dissociative amnesia, and symptoms seen in functional / conversion disorders such as gait problems or paralysis, deafness, voice loss, and sight loss. During compartmentalization, cognitive or bodily processes become inaccessible despite the fact that they continue to operate normally (e.g. no physical or physiological impairment is found) and the processes continue to influence cognition, emotions and behaviour.

Kennerley (2009) conceptualizes different manifestations of dissociation as ‘Tuning In’ or ‘Tuning Out’.

- Tuning In refers to an intense experience or state. Benign experiences would be day-dreaming, or being fully absorbed in some activity. This is in contrast to a distressing flashback memory that cannot easily be stopped.

- Tuning Out refers to “distancing or suppressing an experience”. A state of detachment that can be broad, as in depersonalisation and derealisation, or specific as for amnesia or emotional numbing.

Kennerley’s description is aligned with the model by Holmes et al (2005) where Tuning Out links to detachment, and different aspects of compartmentalization can be described as Tuning Out (e.g. amnesia, emotional numbing), and Tuning In (e.g. traumatic flashbacks). It is important to note that both can occur simultaneously – for example, during a traumatic flashback memory an individual is tuned in to the memory whilst being detached or tuned out of their immediate environment.

Neurobiological models of dissociation

Dissociative detachment has been linked to a specific, protective neurobiological state. During an extreme or threatening situation, Schauer & Elbert (2010) proposed that the sympathetic nervous system ramps up in preparation for action, with adrenalin release leading to physiological responses such as heart rate increase and an increase in muscle tension. If a threat is inescapable the mind and body may move through a ‘fright’ response that includes hyper-alertness, fear and immobility, and then dissociative ‘shut-down’ responses of flagging (emotional numbing, surrender) and fainting.

Nijenhuis & den Boer (2010) hypothesize that individuals with PTSD have a dissociated personality, with an ‘emotional’ personality (EP) that is constantly vigilant and focused on threats, and an ‘apparently normal’ personality (ANP) that is detached from the trauma and focused on day to day tasks and living. These different aspects of the personality are structurally dissociated and underpinned by different psychobiological systems. The EP is sensitive to trauma cues and triggers, and relies on limbic structures such as the amygdala, insula with low activation of hippocampal and frontal regions. The ANP system is characterised by avoidance of triggers and threats, and may be linked to somatosensory association areas in the cortex.

For individuals who experience depersonalisation and derealisation, one neurobiological model proposes that they are predisposed towards an inhibited affective response during stressful situations (Sierra & Berrios, 1998). Here, there is an upregulation of pre-frontal regions and a parallel inhibition of limbic structures and their associated emotional responses. This produces a state of high vigilance (the pre-frontal systems ‘watching’) but a detachment from emotional states that underpins the feeling of disconnection from oneself or one’s embodied experience.

Evidence-Based Psychological Approaches For Working With Dissociation

- Strategies for returning attention to the here and now

Clients can be trained to manage dissociative episodes with techniques such as grounding and cognitive restructuring (Kennerley, 1996). - Trauma-focused techniques for working with intrusive memories

‘Processing’ memories of trauma with exposure based treatments can help to reduce the extent to which clients dissociate. Similarly, approaches which help clients to alter or construct new meanings can help to reduce dissociate symptoms associated with trauma memories. - Cognitive approaches for working with appraisals of dissociation

Threatening appraisals of dissociation (e.g. “I’m losing my mind”) can also be associated with significant distress. Cognitive approaches to depersonalisation and derealization (e.g. Hunter et al, 2003) work to explore client appraisals of dissociation, and Černis et al (2022) suggest that a similar approach may be helpful for people experiencing dissociation in the context of psychosis.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th edn. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Breuer, J. and Freud, S. (1893). On The Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume II (1893-1895): Studies on Hysteria, 1-17

- Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: progress in the dissociative disorders. 6(1), 16–27.

- Černis, E., Ehlers, A., & Freeman, D. (2022). Psychological mechanisms connected to dissociation: Generating hypotheses using network analyses. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

- Holmes, E. A., Brown, R. J., Mansell, W., Fearon, R. P., Hunter, E. C., Frasquilho, F., & Oakley, D. A. (2005). Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(1), 1-23.

- Hunter, E. C. M., Phillips, M. L., Chalder, T., Sierra, M., & David, A. S. (2003). Depersonalisation disorder: a cognitive–behavioural conceptualisation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(12), 1451-1467.

- Kennedy, F.C. & Kennerley, H. (2013) The development of our understanding of dissociation. Ch.13 in F.C. Kennedy, H. Kennerley & D.G. Pearson (Eds.). (2013). Cognitive behavioural approaches to the understanding and treatment of dissociation. London: Routledge.

- Kennerley, H. (2009) Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic dissociation. Ch. 7 in N. Grey (Ed). A casebook of cognitive therapy for traumatic stress reactions. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kennerley, H. & Kischka, U. (2013) The brain, neuropsychology and dissociation. Ch. 5 in F.C. Kennedy, H. Kennerley & D.G. Pearson (Eds.). (2013). Cognitive behavioural approaches to the understanding and treatment of dissociation. London: Routledge.

- Nijenhuis, E. R., & den Boer, J. A. (2010). Psychobiology of Traumatization and Trauma-Related Structural Dissociation of the Personality. Ch.21, p.337-365, in P.F.Dell & J.A. O’Neil (Eds) Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and Beyond,. Routledge, Taylor & Francis, Abingdon, UK.

- Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress. Journal of Psychology, 218, 109-127.

- Sierra, M. & Berrios, G. E. (2000) The Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale: a new instrument for the measurement of depersonalisation. Psychiatry Research, 93, 153–164.

- Steele, K., & van der Hart, O. (2013). Understanding attachment, trauma and dissociation in complex developmental trauma disorders. In Attachment Theory in Adult Mental Health. Routledge.

![[Free Guide] Critical Illness Intensive Care And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)](jpg/_---critical_illness_intensive_care_and_ptsd_en-gb_guides_cover-preview.jpg)