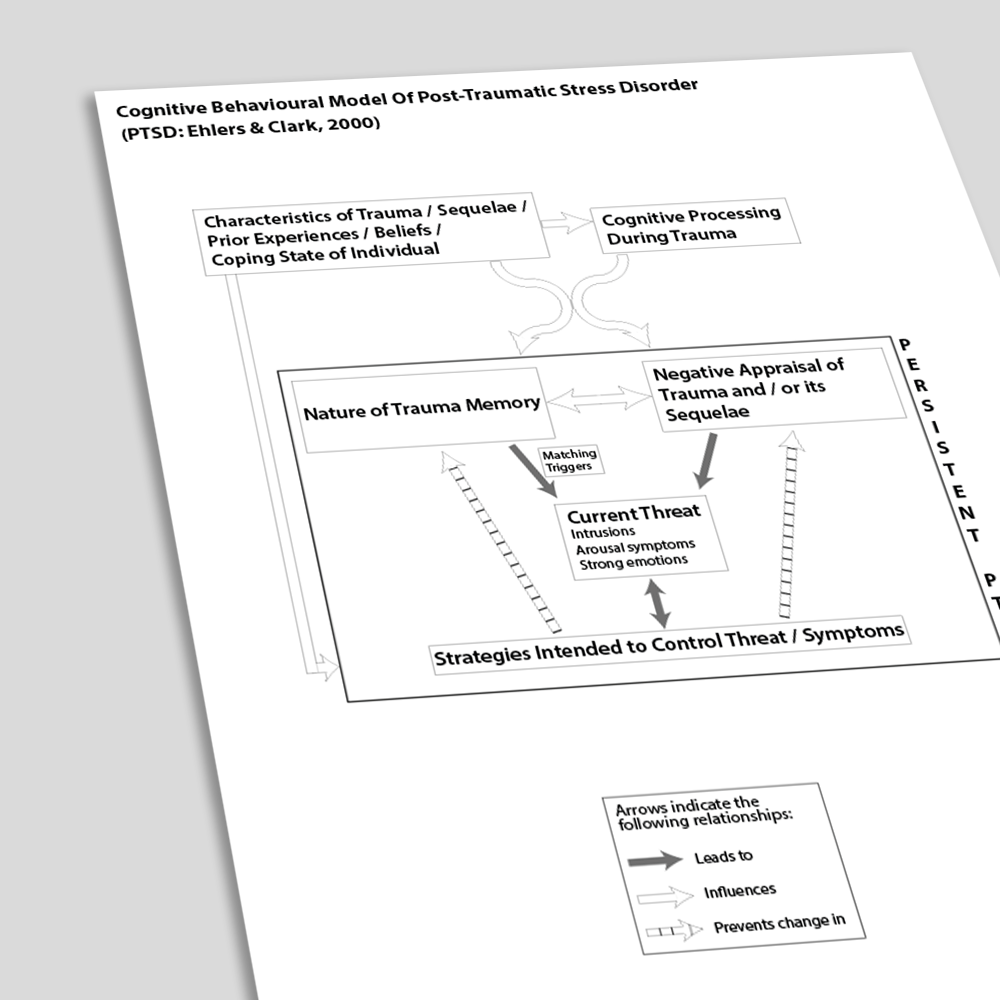

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD: Ehlers & Clark, 2000)

Download or send

Tags

Languages this resource is available in

Problems this resource might be used to address

Techniques associated with this resource

Mechanisms associated with this resource

Introduction & Theoretical Background

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common reaction to traumatic events where a person was exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. Depending upon the type of trauma experienced, approximately 10% to 30% of trauma survivors will develop PTSD (Santiago et al., 2013). Some of the strongest predictors of whether an individual will develop PTSD is how severe they perceived the trauma to be, and the levels of social support post-trauma (Brewin, Andrews & Valentine, 2000).

Symptoms of PTSD include:

- Intrusion symptoms. These are characterized by: recurrent, involuntary and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic events; recurrent distressing dreams where the content or affect of the dream is related to the traumatic event; dissociative reactions where it feels as though the traumatic events are recurring in the present moment (flashbacks); and intense or prolonged

Therapist Guidance

“It would be helpful to explore and understand how your PTSD has developed and what is keeping it going. I wonder if we could explore some of your history, thoughts, feelings, and reactions to see what kind of pattern they follow?”

- Characteristics of trauma / sequelae / prior experiences / beliefs / coping state of the individual. All of these factors can affect an individual’s trauma memories, and how they appraise what happened to them. When formulating with clients, it is helpful to ask the client to label what happened to them, but it is equally important not to probe for too much detail about the trauma too early, as it may lead to unnecessary distress or dissociation, or getting side-tracked. The client can be reminded that there will be an opportunity to talk in detail about the trauma during subsequent stages of trauma treatment.

- Assess the trauma:

References And Further Reading

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Retrieved from http://www. apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- Brewin, C. R. (2014). Episodic memory, perceptual memory, and their interaction: foundations for a theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 69.

- Brewin, C. R. (2015). Re-experiencing traumatic events in PTSD: New avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks. European journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27180.

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour research and therapy, 38(4), 319-345.

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Dunmore, E., Jaycox, L., Meadows, E., & Foa, E. B. (1998). Predicting response to exposure treatment in PTSD: The role of mental defeat and alienation. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 11(3), 457-471.

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of